Bumming Out with Carrère

on Yoga, weed, NYC, and newer friends

I checked into a Times Square hotel, allegedly 3-Stars. After the first night wrestling with the collapsed duvet wrapped in a bed-size paper towel, I walked to Macy’s and took the elevator to the 6th floor, bought a comforter and two pillows on deep discount, then trundled back through Midtown tourists with my puffy loot. Those sidewalks are always packed, but on a winter weekend before Christmas, they’re fully sardined. The slow shuffling was all the more awkward for my wide load. The new bedding just barely improved the situation in my room, but you can’t expect much for $98.

When you visit New York and ask people to hang, the requisite question is Where are you staying? When I answered Times Square, the unanimous reply was WHY?! It wasn’t my pick; my room was booked and paid for by the person I was primarily in the city to see. They were also visiting, stationed in Midtown against their better judgment for convenience of other commitments in the area.

I’m still spoiled from years with a company credit card and the blessing to book rooms with foolish rates in cool neighborhoods, but I’ve got an old soft spot for Midtown. On my first trips to New York at the beginning of my career, self-employed and traveling on my own dime, I stayed at the Hotel Wellington on 7th and W. 55th. The rooms were tiny, no space between the bed and the walls for my suitcase, so I stored it in the shower. I often ate at the diner on the corner, alone in a booth, amused by the $7 price tag on a small dish of cottage cheese. But why am I telling you about hotel rooms?

I know that these memories interest only Anne, the boys, and me, that we’re the only four people in the world whom they can make smile, or cry, but too bad, too bad for you, reader, you’ll have to put up with the fact that authors relate these kinds of things and don’t delete them when they’re rereading what they’ve written, as would only be reasonable, because they’re precious, and because one reason to write is also to save them.

— Emmanuel Carrère, Yoga

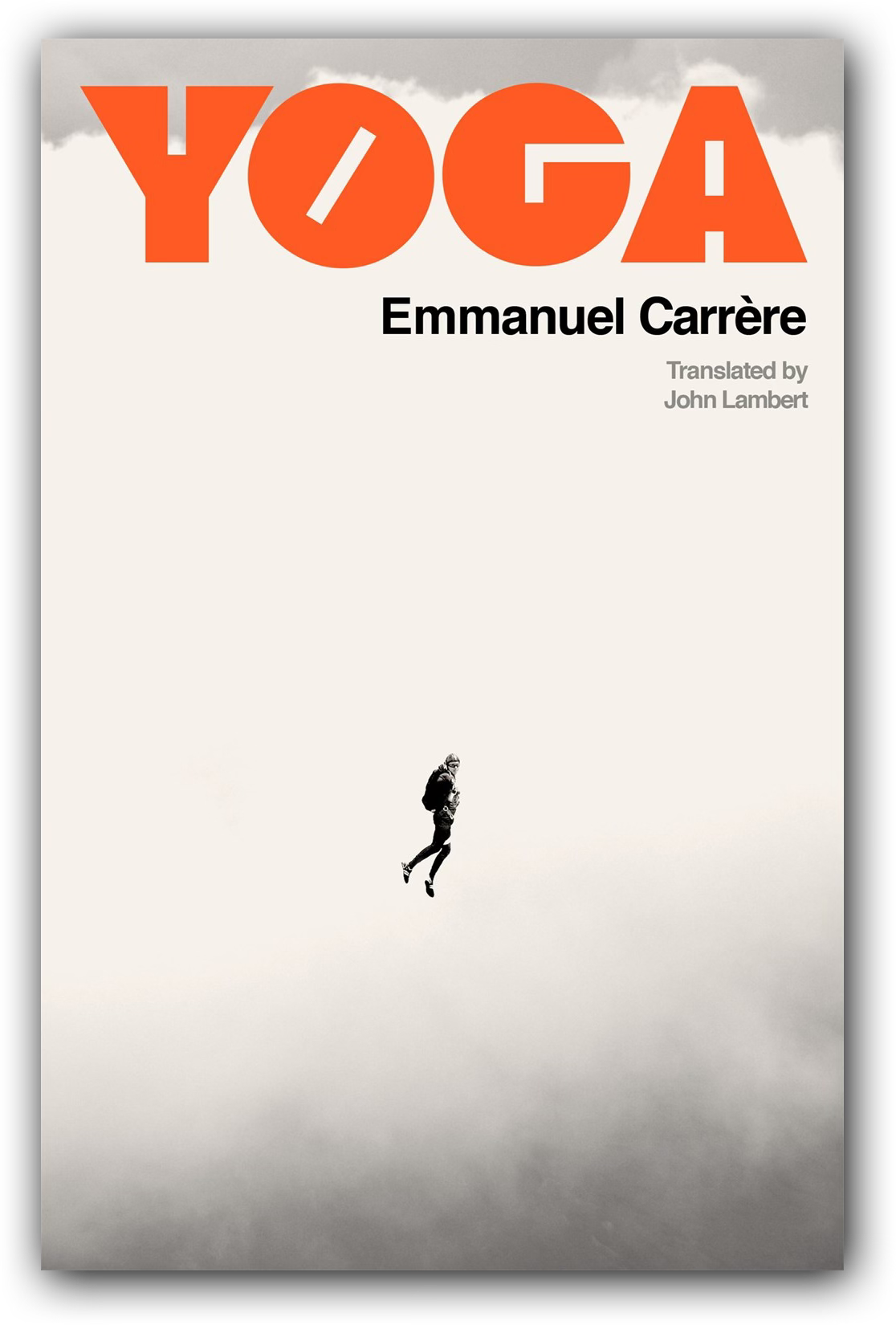

Carrère begins his book Yoga at a 10-day silent meditation retreat. He’s a mediocre meditator (he uses the words yoga and meditation interchangeably) and practices tai chi, so Carrère’s there for genuine practice, but also to write a book—“an upbeat, subtle little book on yoga”—that could be found outside the self-help section of a bookstore. It was my first time reading Carrère. The writing is wonderful, and the subject, I told myself, was timely. I’ve dipped into meditation before, fucked around with various apps and teachers for beginners, but it’s never stuck. Given my current state of mind (more later), I need to try something, maybe try something again, so the book was enticing. Carrère talks meditation with a light touch, humor, self-deprecation, and a shake of cynicism. In one section, titled Meditating while drunk, he describes an earlier period in his practice.

When you’re drunk or stoned—I was often both—you think you’re finding nuggets of gold, then you come down and realize they’re lumps of turd … Meditating while drunk is absurd, I agree, but at the time I persuaded myself that I was observing my drunken state. Because the interest of meditation … is that it awakens a sort of witness inside you … Of course, alcohol and drugs turn this secret agent into a double agent who can’t be trusted. Nevertheless, I didn’t stop meditating, I’ve always more or less kept at it, and if I persist in writing this book it’s to say that those who practice the martial arts, Zen, yoga, meditation, all the big, radiant, beneficial things I’ve sought all my life, are not necessarily wise or calm or serene, but sometimes—often, even—pathetically neurotic like me, and that that doesn’t prevent them from, in Lenin’s strong words, “working with the available material,” that in fact you have to do just that, and that even it it doesn’t get you anywhere, you’re right to persist on this path.

Here is permission to be bad at meditation, to not reach the higher plain, to simply try. This isn’t new; all gurus, teachers, and self-help influencers say shit along these lines, but it’s the first time I’ve seen it presented in literature. I told myself the book was written just for me to be read at just this time.

I arrived in New York un-stoned, having not smoked weed for several days. With scant confidence in success, I’ve told myself that my daily driver for decades has turned on me, and now it’s time to move on. It’s not just that I smoke so much I hardly get high, that my sleep is bad, the lack of dreams, the loss of memory, the junk food cravings, the racing heart and body aches. It’s not just that my 3-year-old daughter now recognizes why I constantly step outside… I’ve also become the angriest stoner I know. I’ve been told by more than one therapist that anger is the go-to emotion for covering up deeper and more complex feelings. My current guy suggested that I might not be angry, but sad or scared. I had no idea what the fuck he was talking about because, as I’ve come to realize lately—late late late—I’ve spent my life avoiding feeling much of anything. I’ve used weed, of course, but also work, reading, writing, traveling, and shitloads of thinking to sidestep my feelings.

I’ve taken weed breaks before; a few months off now and then. Twenty years ago, I quit when my ex-wife asked me to, but it wasn’t long before I was back on and hiding it from her. I quit for a while when I had chronic pain and the doctors wouldn’t prescribe pills unless I peed clean. When Mal and I were trying to make a baby, I quit for a bit to foster more sperm, stronger swimmers. Lately, I’ve paused a couple of times to see if it reduced anxiety. It did, of course, but with each quit, I had every intention to start again after a reset. The first joints sparked after being away are still magic, like you remember from when you were young: goofy and loose and fun. But my return was always full-on, perma-stoned, wake & bake and bake all day. You could call it devotion, but you should call it addiction.

While Carrère’s off paying attention to the breath, jihadists attack the office of Charlie Hebdo in Paris. Carrère’s close friend Hélène was romantically involved with the writer Bernard Maris, who was killed in the attack. Carrère was a newer friend to Maris by association, but he knew and admired the man’s work, and Hélène wanted a fellow writer to speak at the funeral. She interrupted the retreat on day four and asked Carrère to come, so this little book about meditation becomes something else. After the funeral, attempting to return to his yoga book, Carrère struggles with friction between his silent sequester and the bloody horror that happened outside, and he’s glum. He soon finds the horrible bottom of a sinking depression, and we get part three of the book, “The Story of My Madness.”

Carrère fought bouts of depression all his life with therapy, with time, and, I suppose, with meditation. He’d been enjoying a surprising 10-year stretch of stability. When his old friend darkness returned with a vengeance, he decided to visit a psychiatrist for the first time.

It’s disturbing, at almost sixty years of age, to be diagnosed with an illness that you’ve suffered from your whole life without it ever being named. Your first reaction is to protest. I protested, insisting that bipolar disorder is one of those notions that are all of a sudden in vogue and get pinned on anything and everything—much like gluten intolerance, which so many people discovered they suffered from as soon as people started talking about it. Then you read what you can on the subject, you reexamine your whole life from that angle, and you realize that the shoe fits. Perfectly, even. That all your life you’ve been subject to this alternation of excitement and depression that is of course the lot of us all-because all our moods change, we all have highs and lows, clear skies and dark clouds—only that there’s a group of people to which you belong, along with, it seems, 2 percent of the population, for whom the highs are higher and the lows lower than average, to the point that their succession becomes pathological.

The diagnosis was Bipolar Type 2. I wasn’t aware there were options. Type 2 is not the one that makes you “strip naked on the street, or suddenly buy three Ferraris,” and I recognized myself in the description of the disease, and so it seems that stuff other than weed can make my heart race. I freaked out a little bit and set the book aside.

I guess I’ve traveled to New York… 75 times? 100? Traditionally, I went to see concerts, musicians, and folks in the music industry almost exclusively, but now I try to make newer friends, an embarrassing endeavor. It’s a big ask: Hi, are you up for a trial period with me? People have their people already, but unfortunately for people, I’m horny for relations of the literary variety instead of indie rock singers and show promoters. This has been my social project for the last few years, and it’s not been without setbacks. I’ve inflicted some harm—alienated, offended, and let people down.

In the spring, I spouted off aggressive, unwelcome, and unqualified publishing advice to a newer friend. I went in hard, and now they don’t want to talk with me about writing anymore. This was a major loss, heartbreaking, as talking to them about writing had become one of my favorite things. In the summer, I said something judgmental and resentful, or at least that’s how it was received, to another newer friend, an editor I had come to love. I was left on read, unfollowed, unsubsubscribed. One strike and I was out—no discussion, my apology unaccepted. Recently, a writer I admire was gravely disappointed with the results after I published a piece of their work. They took the opportunity to say some unkind things. An apology arrived the next day—honest and pure, which I accepted immediately—a massive relief. We moved on, things are okay, but the relationship has changed. Fewer texts, colder replies, less joking, less everything, and it’s difficult to imagine being given the opportunity to publish their work again. Each of these hurt like a motherfucker (look: feelings!), and I can’t help but think the damage is eternal, that forgiveness is weak, but who knows. I still reached out to potential newer friends in NYC and had some good hangs.

In fact he loved literature above all else, and that’s basically all we talked about during the—what?—five or six times we had dinner together. We were in no hurry, we were slowly becoming friends, we had time.

I packed Yoga in my bag for New York, but didn’t read a single page. I often struggle to read while traveling, and I was content to spend more time thinking about what I’d read up to the point of Carrère’s diagnosis. When I got back to Nashville, I started again from the beginning and read straight through to the end. Then, I read it again.

After his diagnosis, Carrère’s depression became dangerous, life-threatening, and he was institutionalized. He’s treated first with Ketamine, then electroshock therapy. Each time he wakes up after getting zapped, Carrère finds himself staring at a reproduction of a painting, a beach scene, hanging on the wall of the recovery room.

This beach, this painting, this poster, are for me the saddest sight in the world. Not just the saddest, but also the most frightening. I hope to never see them again.

I wonder if my version of this poster might end up being the cover of Carrère’s book. I sink further into my own pit after my trip, and I’m still down there. It’s two weeks now without weed, and I could probably blame my mood on withdrawal, but I’m beyond suspicious that it’s something more. But don’t worry; I’m not going to let French literature diagnose me. I’ll take the same step my new favorite writer took and make my first appointment with a psychiatrist.

When I used to quit cigarettes—I did it many times—the smell would often call me back, and I’d go buy a pack. I’d tell myself I’d just have one, then smoke 30,000 over 3 years. It was another book, a real-deal self-help title, that finally helped me kick cigarettes, and eventually, when a smoker would step into the elevator or get behind me in line at Chipotle after sucking down a stick, I found the smell repulsive. I was pleased to find that in NYC, which reeks of weed on every block, I was not enticed to find the nearest dispensary.

That said, I did stink all weekend. On my first day there, I stopped for a pretzel at a cart on the corner of 6th and 42nd. While I waited to order, a cumulus cloud of halal meat smoke engulfed me and sank into the down of my coat. I caught whiffs of it the rest of my time there. Apologies to newer friends whom I hugged hello and goodbye.

Thank you for this, Adam. Such a beautiful piece.

For what it is worth — oh no, here comes some unsolicited criticism/advice, which may alienate you from me and vice-versa, ha ha—, I left reading your post really wanting to learn more about you.

There’s some moments you’re so candid and vulnerable: “You could call it devotion, but you should call it addiction.”

I also really love the interplay between Carrère’s story and your own. And whereas he started dabbling with yoga/meditation, stumbling into a diagnosis of depression, then ending with severe treatment (and fear of the treatments), you’re just walking into the door of your own diagnosis.

I realize as I write this that there’s not much more you could share right now - you’re still in the process of learning what this means for you. So I suppose this really is not criticism. Rather, let’s call it a gentle invitation (without any sense of entitlement) that you write more about this journey when you’re ready to. I’ll be waiting to read more!

I love this, Adam! Been looking for my next book to read and this sounds like the winner!