Glennon Doyle for Men

What is this? Memoir in essays. Manifesto. Self-help. Spiritual direction. Gobbledygook. It’s post-genre, like music playlists now. It’s definitely pop/stream/pod-culture zeitgeist hitting stuff with high-fives from Reese, Brené, Oprah, Adele, etc.

There are so many things I could hate/have hated packed into “Untamed” and the aura around it. I don’t know when I got soft enough for this, but give a ton of credit to my wife, the same way Glennon sometimes does in her story.

This book is about integrity, a word I’ve overused since I stumbled into Midwestern hardcore kids in high school. I was *checks calendar* a few days from 46 years old when I learned the definition, which Glennon lays down early in the book talking about those who possess it.

They are not divided between what they feel and know on the inside and what they say and do on the outside. Their selves are integrated. They have integrity.

DUH, right? But I couldn’t have said it that simply. Later in the book, she puts it another way: “Integrity means having only one self. Dividing into two selves—the shown self and the hidden self—that is brokenness.”

Glennon’s agent works in my office and gave me an advance copy in January, a lifetime ago, along with a bunch of other cool upcoming titles in a cardboard-box care package. She made a point to highlight “Untamed,” saying “I don’t know if it’ll be your thing, but I’m really excited about this one.”

I thanked her and set the box next to my desk. I planned to take it home and mix the books in with the three thousand others on deck, then proceeded to step over and around the box for many weeks, including on the afternoon in early March when I bailed on the office to start working from home a few days before it was mandated.

I went back many weeks later, a quick in-and-out to rescue my previously impressive Fiddle Fig tree. It was down to a lone leaf up top due to a lack of water. I brought it home and grabbed the box of books, too, and finally picked up “Untamed” recently.

Ok, here’s a book my mom would have read and freaked the fuck out about had she not died. She would have eaten this up, I think, like she did with Evangelical Christianity when I was little, and later other religions or religious-adjacent things. I can imagine her going on and on about Glennon to her friends on the phone in the kitchen, singing her praises on repeat as she moved down her call list. Today she’d be texting or posting, charged up to make some changes and fessing up about her history of homophobia in Jesus’ name.

Teenage Adam would have been annoyed with her, for sure, but now it’s a book I’m telling my sister to read, and as soon as I’m done checking my notes and dog-eared pages while I write this, I’m gonna pass my copy to my wife Malory.

Through my unscientific web-search survey, I’ve yet to find a published review of this thing written by a dude. There are zero (0) blurbs by men on the book’s website. On Goodreads, I found just two guys commenting as I clicked through the first 10 or 15 pages of reader’s reports.

Glennon wrote the book, to be sure, for an audience of women. Was I not supposed to find this? Am I intruding? Maybe, but I read it and liked it, and found much to relate to. Other guys should check this out, especially those cut from ‘80s Christian cloth, dads, ex-assholes, and divorcees.

The book is not political or academic, it’s anecdotal and conversational. It’s not self-serious. It’s irreverent and funny.

I am a sensitive, introverted woman, which mans that I love humanity but actual human beings are tricky for me. I love people but not in person. For example, I would die for you but not, like ... meet you for coffee.

So, early on I found myself aligned with this woman. She’s got a big clear voice and vibe, which reads true to me if not a little cringey sometimes with the previously mentioned gobbledygook. You will have to tolerate lots of Power, Freedom, The Knowing! etc. Keep in mind her previous two books both have the word Warrior in the title. But don’t worry, you can do it. I did!

Not surprisingly, I was drawn to the stuff about Glennon losing her religion, and there’s a good bit of it in here. The book’s core is the story of Glennon falling in love with a woman, whom she marries, after leaving her husband and her Christianity. The place Glennon has landed sounds lovely, even with the weird platitudes.

God is not a being outside of me: God is the fire, the nudge, the warm liquid gold swelling and pressing inside me.

GROSS! But I mean, I think I agree ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. It’s taken me 20+ years to get over the centerfield line between guilt and confidence, between fear and ease, to be able to say something like: Yeah I guess I sorta think we’re god, you know, you and me.

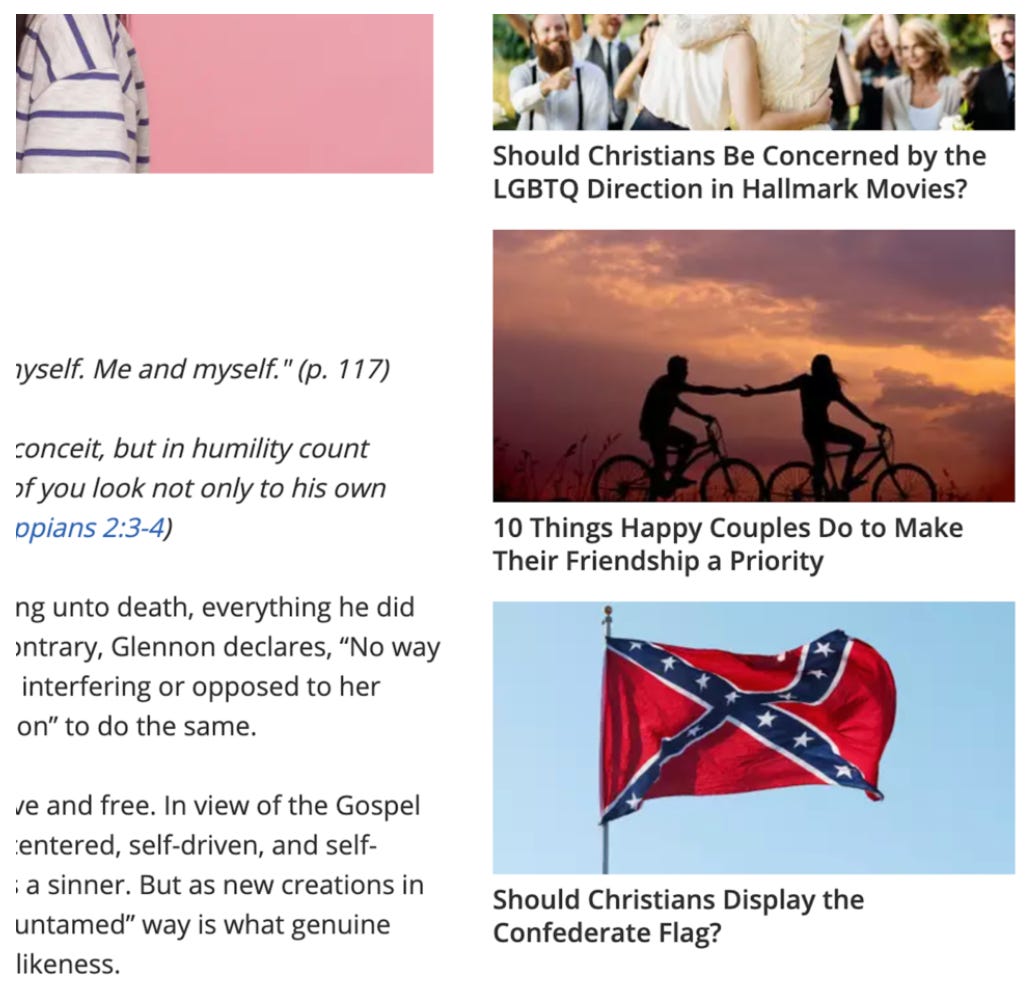

I found a very bad take on a Christian website highlighting the book’s anti-Christian views. See here a screenshot of the sidebar links to other stories on their site. Thank you, Mrs. Cro*swalk.com writer and Mr. Cros*walk.com website editor, for your clarity.

I also perked up for her stories about parenting, as I’m navigating fatherhood with a newly high-schooled teen, a long divorce which is more permanent than marriage, apparently, and trying to have a child with Malory.

I cried the entire way through the chapter called “Elmers,” where Glennon fights her shitty parental impulses, briefly succeeding in stopping her helicoptering and getting to witness her daughter grow, evolve, and move independently as she finds her unlikely place on a sports team.

Now the goal of parenting is: Never allow anything difficult to happen to your child ... [which has] led us to steal from our children the one thing that will allow them to become strong people: struggle.

Her stories of the way she was parented, the way she has parented, and the way she wants to parent are humble and touching. It’s these parts of the book, which are both forgiving and aspirational, where I feel the author is the most self-aware.

If there’s an action item in the book, it might be to simply imagine, which is a bummer given the recent flat-tire use of that theme on Instagram by celebrities, but if you can blot out the memory of those faces on your little screen, Glennon makes a good case for it.

Imagination not only is the catalyst of art, it's also the catalyst of all kindness and connection. Imagination is the first step on the bridge of compassion. It is the shortest distance between two people, two cultures, two ideologies, two experiences.

There’s a criticism out there that the book ignores the elephant in the room; that Glennon is a wealthy white woman, so turning into a wild cheetah (the opening essay is about a big caged cat wanting to be free) and living by straight imagination is sorta easy. I don’t like this critique, maybe because it’s even easier for me. I’m sure she’s rich and we know she’s white and the cheetah thing is… imaginary! I will say the book is very very very mainstream, and I think that is a good thing.

Oh, and my plant is recovering. The tall trunk is still bare, but at the very top where there’s a grip of new leaves quarantined above that last one standing from the spring. It’s giving the tree a weird new silhouette. It’d probably be ashamed, if a plant could be, but I like the way it’s standing in the living room now, awkwardly.