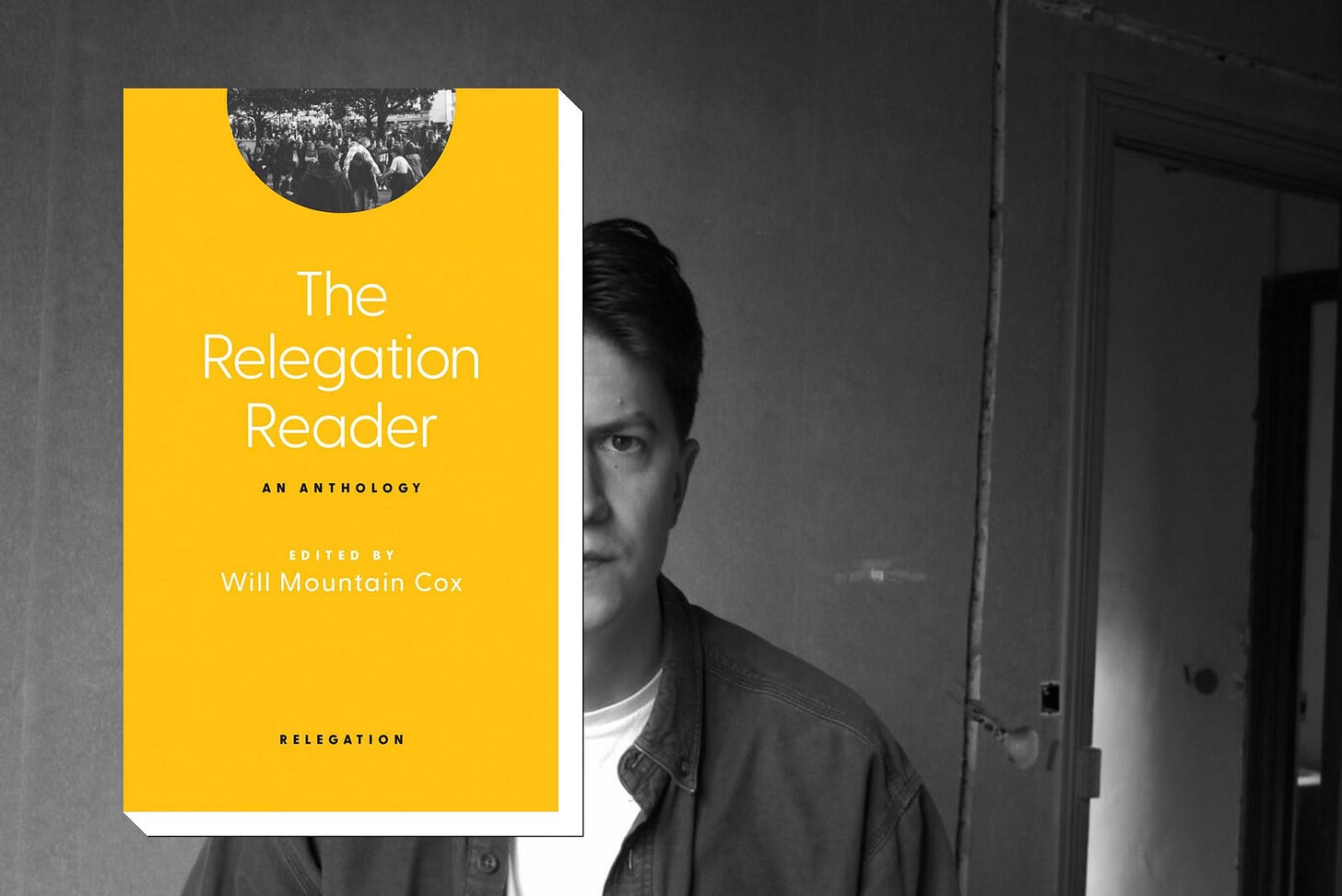

Review: The Relegation Reader, edited by Will Mountain Cox

“Of the time we are alive. Of the books we write in the time therein. And of the books we read.”

Will Mountain Cox says WHAT ARE THE STAKES of literature, then drops a dizzy list of all that comes with the search for an answer: the magazines, the parties, the postings, etc. I count a few shots taken at me myself and I, a writer and publisher and poster, and probably at you as well, but it’s a playful and perceptive opening to a long letter to the reader and a beautiful account of where we are right now. What are the stakes “Of the time we are alive… Of the books we write in the time therein. And of the books we read.” He goes deeper on that last one, the reading:

Of the books that will never die, written by humans who always will … not of the writers living, but of their work alive, written in our time. Of the time therein, with us as living readers. Of the stakes inherent to reading. Of the inherent stakes in reading the work of living writers. And as readers, marking their work immortal.

Look at that shit! This dude is saying that readers make literature eternal, not writers or publishers. Most people fuckin’ around with underground books and magazines are writers and/or publishers themselves, but WMC ignores this and lives in a world, in fact makes us a little world, where readers simply read. Even if almost everyone holding a copy of The Relegation Reader is a writer or publisher, the collection asks us first to be readers, and to get stoked on the deadly-serious and very cool power that holds.

Daniel Levin Becker opens the anthology with two list poems, and I’m relieved that they are funny. There’s a good snark in WMC’s intro—“every new piece of literature being so funny”—but I’m laughing at lines from poem number one, “Exercises in Pornography”:

They keep getting sidetracked explaining their tattoos.

Playback is slowed down 1,000 percent.

Golf spectators.

I’m surprised by the McSweeney’s-ness of funny list poems kicking things off. Is McSweeney’s out of favor—a GenX success story gone boring? I don’t read it anymore and see that the new issue comes in the form of a Trapper Keeper, so I get it, but I can’t deny what that camp offered as I graduated with my state-school English degree in the late ‘90s. It was bonkers and foundational for me.

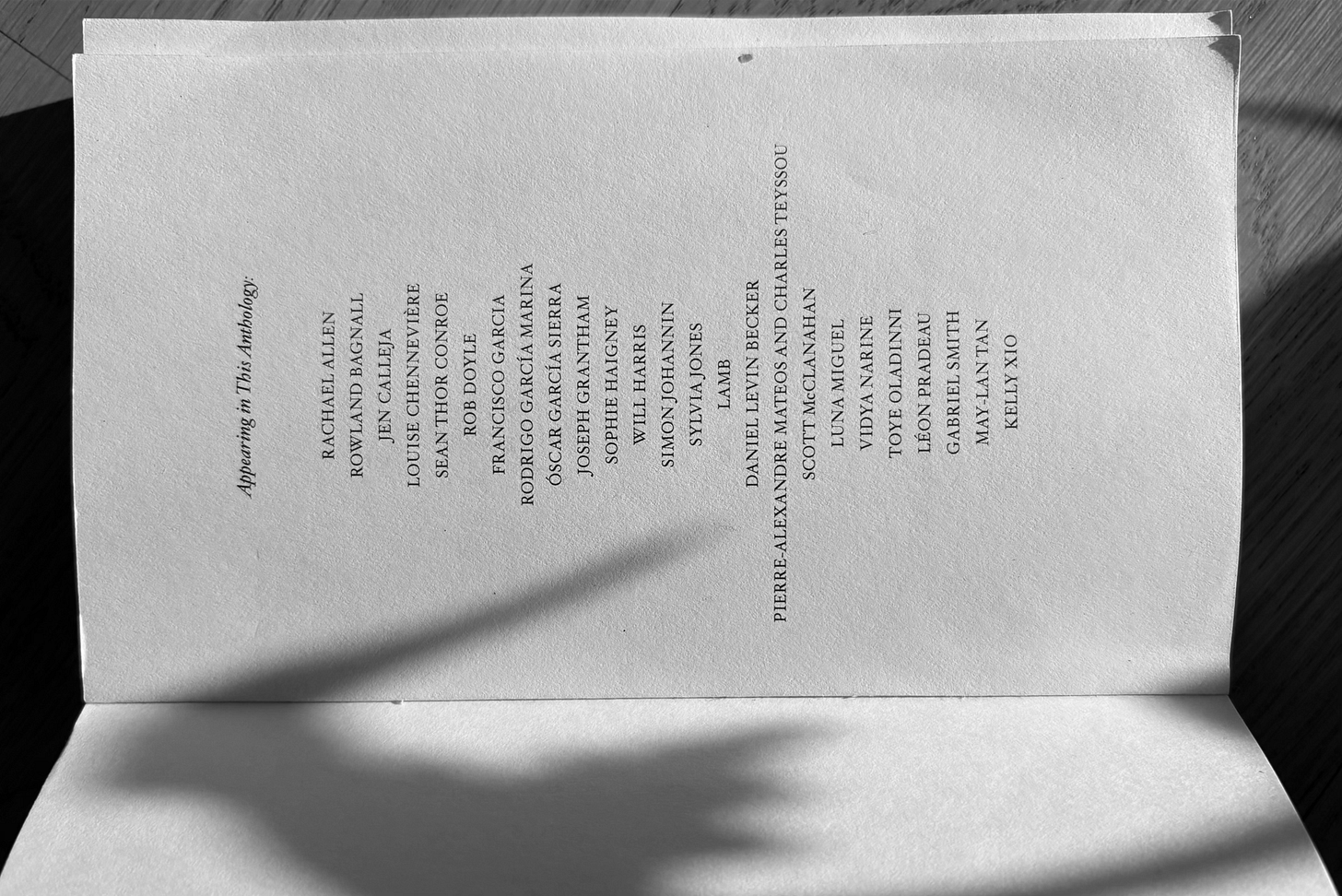

After the opening poems, I find two pages of generous editorial, guard rails that appear 25 times throughout the collection. WMC explains his relationship to the writer’s work, essentially why he wanted them included, recommends more of their writing in other books and magazines, and then like your Choose Your Own Adventure books from childhood, offers three or four suggestions on what to read next in the anthology. I played along, did not go in order, and jumped ahead to Joseph Grantham’s poems. Joseph edits R&R, the literary magazine housed under the Relegation roof, but this is not mentioned, which is awesome. Across all the editorial interjections, WMC won’t even mention once that he’s a writer himself. Who among us has the restraint?!

After two poets to start, I take the path marked Jen Calleja for an excerpt from her novel, Vehicle. The setting is post-something—WWIII? Pangea 2?—and it’s certainly post-punk, and like a magnet I’m drawn to Hester Heller as she proposes going undercover to gather intelligence and spread propaganda via lyrics in now foreign and probably dangerous lands as a touring musician. I wonder whether Heller’s plan to use her band as spyware has Ian Svenonius/Nation of Ulysses DNA.

THE CHAIR: What exactly does a band consist of and why would they tour? Wouldn’t it draw attention to you?

HESTER HELLER: A band is a group of narcissists playing music together. A tour is basically a vehicle for them to travel the world without necessarily engaging with other cultures and enjoying the benefit of receiving special treatment for apparently no reason other than working for about twenty minutes a night.

SO funny, so harsh. I can name exceptions to the rule, and I take issue with the 20-minute thing, but I’ll be reading this novel in full. I ordered it, it’s already arrived, and the book looks and feels sick. I’ve been avoiding “band books” the last year or two while I wrote my own. During that time, I saw some disparaging remarks about the sub-genre, but lately I’ve put my antenna back up and see them everywhere.

I do the Léon Pradeau poem, a music essay from Louis Chennevière (very Substacky), and May-Lan Tan with WMC’s near shark-jump story of living on the floor at Shakespeare and Company and stumbling upon Tan’s first book, reading it front to back through the night.

Onto another excerpt from Vidya Narine’s Orchidist next, in which she describes “a Bluetooth earpiece screwed in tight,” and it’s a good reason to read work in translation, to know that people are lame everywhere, but Narine shows the flower shop customers in the story much love.

One day, before my eyes, Yannick gave birth to a hybrid he dubbed a Mnemosyne, after the Greek goddess of memory. It was a deep pink Phalaenopsis whose flowers lasted a particularly long time. He had created it, he told me, in honor of a customer who had become a friend. A famous actor who kept forgetting his lines, and then all the rest, too, as he got older.

I get excited each time a piece is tagged as an excerpt, and I’m hyped that many come from books already published, and not this month or this year. The promo window for these books closed long ago, and now these late-comer excerpts! I love this. We need more of this.

I went to the Rachael Allen poems, then to Lamb, who contributes my favorite poems in the anthology. The internet anonymity has been a roadblock for me, but I’m into these tender pieces about small children and God stuff. I’m surprised by my openness to God in contemporary reading this year.

I hit the Roland Bagnal poems and “So begins a love story” by Simon Johanna. At the end of that one, WMC suggests Sean Thor Conroe for another love story. Sean’s podcast with the novelist Harold Rogers is how I know of WMC—they had him on to discuss his novel Roundabout, a slim book about Paris and friendship that I bought, read, and loved. Harold and Sean have gone Biblical as hell on their pod the last few years, heavy on Jesus and the under-discussed Ladies of the Scriptures, so a carpenter not ignoring a prostitute while traveling on common public transit in “Money” is no surprise. In his note after the piece, WMC says Sean “attempts to pull canon-energy into modern parlance,” and that’s exactly what I love about their podcast, too. I’ve tackled a bunch of difficult books empowered by their stoney baloney chats.

I pick the path to Rob Doyle next, a prose poem, I think, LCD Soundsystem’s “Losing My Edge” + reincarnation, and another list in its own way. I pass through more poems, Sylvia Jones and Luna Miguel, and now at the end of the pieces, sometimes the Choose Your Own options point to things I’ve already read, so I pick from the table of contents. I did the only collaborative piece, Pierre-Alexandre Mateos and Charles Teyssou’s wild thing, but too wild for me at 4:30am on my first coffee.

I paged to Francisco Garcia’s “James Henry Corbitt,” and didn’t recognize the proper name of the story’s title, unsure if I was reading fiction or history, but cool with either answer:

James Henry Corbitt killed his mistress in August 1950. On trial in Liverpool three months later, the 38-year-old engineer didn’t bother protesting his innocence, though his guilty plea came lodged with a defence of insanity. Unfortunately for Corbitt, the prosecution had uncovered his diary, which laid out the murder plot in allegedly clear-minded detail. Praying for one more chance… to finish her off… Always seem to be in trouble, mental strain, losing control of my brain, think my brain is turning, must be what I was afraid of. On being convicted and sentenced to death, he was taken to Manchester’s Strangeways Prison, the redbrick Victorian monster looming against the fringes of the city centre.

I see the word research on the next page, so this is a true story about Corbitt and about Britain, and I would like to read more about Britain from Garcia.

I moved from the U.K. to Sophie Haigney’s San Francisco piece, her writing making the city Beat again?! I lived in Oakland after college in 1998, an exceptionally lame time in the Bay Area when the Yahoo! billboard was more a landmark than City Lights, and I found none of the romance I read in Kerouac or heard the Easy Bay punks sing about. I worked wack jobs for a year at different tech start-ups, both scams, then bailed for Seattle. Sophie might be onto something new or resurfacing there.

After Will Harris’s essay on a good death, I read Scott McClananahn’s excerpt from his upcoming book. It takes place in the city, not mountains or the hills, which is fun to see and it’s Giancarlo DiTrapano lore, seemingly in good hands. WMC draws a connection between Toye Oladinni’s piece and Mrs. Dalloway, a book I read recently for the first time. I can see it—writing London, updated with Uber—but the connection I found was Toye and Scott’s stories both set in a world of writers, going to writerly parties. It worked for me with Scott’s excerpt, but kicked me out with Toye. Still, 50/50’s not bad for writers writing writers.

Gabriel Smith says what his story’s about from the start: true faith. In fragments, the narrator recounts letters from an unnamed she, a world traveler sending updates from everywhere: Argentina, Saint Petersburg, Halberstadt, and Dubai. I see the faith thing throughout; it’s not subtle and it’s satisfying, quite nicely done, but I’m struck most by the sadness in the piece. I might say it’s the saddest in the collection. I get the sense the letter writer is traveling alone, and whoever’s receiving the letters is lonely waiting.

I struggle through Rodrigo García Marina’s experimental Covid poem, the most formally challenging of anything in the anthology, then read Óscar García Sierra’s story. I see that I’ve written a cryptic note at the end: What are the bricks? I skim for an answer and I remember the zit on the narrator’s nose. Unfair to Óscar to be sure, but it bothered me like farts bother me in stories. I even hate the farts in A Confederacy of Dunces. Kelly Xio is the last stop on my adventure, and I like her long prose poem which is diarist-adjacent and computery. I remind myself to read work referencing YouTube and modern drugs lest I age out.

SO OKAY, it’s a rave review. I’m in for the whole anthology, even the stuff not quite for me. I revisit WMC’s letter to the reader at the beginning, and find a new pull-quote to love. Recounting the start of an earlier publishing endeavor, WMC says:

James and I began a literary magazine … under the assumption that old and immortal books were great, but someone had to make our peers old and immortal too … we could read these young writers’ work, and by doing so their writing would become infinite—to us at least.

That magazine doesn’t publish anymore, but clearly the mission is alive and you can MAKE SOMETHING ETERNAL.