The Lonesome Crowded Karlstad

Pics & Captions from Sweden, Pt. 3

“I told the twins you’re coming to Karlstad,” Niclas said on the phone before the trip. “I told them you don’t travel internationally so much, and they said, ‘Well of course, he’s American. That place is so big and there’s so much to see; why leave?’”

Niclas is kind to me. I’ve got to believe he’s either made it up or polished it up in translation.

He must be the most offline person I know. It’s a betrayal to write about this fuckin’ guy on a website, to post a bunch of photos of him. I’m going to pretend I’m writing about Karlstad, but this is really an online review of my Swedish friend.

Brian, Niclas, and I woke up after the Bon Iver show at Dalhalla and grabbed some yogurt and sandwiches from the grocery in Rättvik before leaving town.

Niclas led in his car, and picked a road he’d not used in a long time, a prettier route home. Brian and I noticed the lack of billboards on the highway. It’s not zero billboards, but it’s almost zero billboards.. I thought back to the show at Dalhalla the night before. No ads. No sponsorship banners. Even the vendors had tiny signs.

The drive was gorgeous, any direction you looked. Niclas pulled over, walked to our window, and said he remembered a place for coffee and ice cream. At the next right, we took a narrow road and climbed up and up and up. We parked at the top and got one of the best vistas of our time in Sweden. “This is where I grew up,” Niclas said, looking down into the valley. Brian took a 360° video. Don’t miss the living roof on one of the outbuildings at the end.

The cafe was closed for the day when we arrived, but Niclas knocked on the backdoor and turned up a friendly woman who was about to lock up and leave. She rummaged around for an impromptu snack, a few cakes and boxed orange drinks, and Niclas gave her some cash before she rolled out.

I’ve tried to visualize Niclas’s house many times. For fifteen years, our phone calls have run through his landline in his basement office, and I had a cloudy picture of what it might look like in there. I knew the place was old; turn of the 20th century. I knew there was a defunct restaurant his parents used to run down in the basement, too. I knew there was a lake. I’d never seen a photo; didn’t know it was yellow.

We arrived, we got a tour of the vast, weirdly-organized collection of rooms with a large footprint downstairs, and two separate sections up top connected by an outdoor walkway. It’s flocked wallpaper everywhere, original carpets and hardwood floors. I’ve got a friend who will call my writing lived in when it’s really working for him. This house is lived in, big time. Over one hundred years of settling, aging with various families, tweaks and repairs, the ghosts of an old local business, and modern stuff for teenage boys here, there, and everywhere.

I didn’t take photos of the closed restaurant. I had planned to do it with a different camera after we got the tour, but it never happened. The ex-dining room was crowded with dusty tables pushed against one another, and there was an army in formation of very cool chairs with stained and worn upholstery. We discussed shipping ten of them on a boat to Nashville.

There was an old menu; Niclas translated it for us. The cold kitchen was industrial with no frills. On a prep table behind a rack of china and glassware the size of a bronco, there was a turntable and two crummy speakers.

“You listen to records in here?” I asked.

“Yup.”

There’s a recording studio tucked away down there, too, a proper control room wide window looking over a small live room, and an isolated closet for vocals. It had everything except the gear, the microphones and amps and cables. “Someone borrowed it,” Niclas told me.

There were other rooms downstairs which were no longer restaurant-related. A ping pong table had taken over the common area where a host would’ve greeted you. There was a sewing nook. I can’t overstate the seriousness of the wallpaper in this house.

Spotted a Blank Range “Phase II” cassette in the office. Niclas had heard the tape in 2013 and offered to release it on vinyl via his label Gravitation. He’s put stuff out slowly and quietly for 30 years.

“I’m not going to do anything,” he said. It’s as anti-industry as it gets. “I’m not going to do anything, but I’ll make the record.” And so there’s a 10” piece of wax for this classic nugget no one’s heard with a Gravitation logo alongside the band’s own Sturdy Girls insignia. One of the best recordings of drums that I know.

Upstairs, the house is all domestic. A well-worn kitchen, the bedrooms, the chairs and sofas, a family’s stuff.

Beth and the twins made us dinner and a fruit cobbler, and we ate it overlooking the lake. I thought about the surprising call from Niclas years ago: “We’re going to have some kids!” I heard it immediately. Plural! Not too long after, I went to Beth and Niclas’s wedding in Brooklyn. I left too early into the reception, something I’ve always regretted.

I didn’t get as much time with Beth as I’d have liked. She and Brian got in a great hang, gabbing on the patio one-on-one in the evening. Brian had an acoustic guitar and was strumming three or four out-of-tune chords.

In another part of the house we never really hung out, there’s an untouched renovated kitchen and a small living and dining area with new hardwoods, perfect modern paint and wallpaper. I’m told they’ve tried to move into it a few times, but it hasn’t stuck.

Here’s Niclas in his old kitchen, my favorite photo from the whole trip.

Karlstad is the 20th-largest city in Sweden. For scale, it’s like Bloomington, Indiana, only Karlstad University has 16,000 students while IU’s got 50,000. Like each place we went, in Karlstad there was a shocking lack of human density.

But to Niclas, the place is changing. His house used to be one of only two on the hill. The other one, a mansion built in 1720, had all the land save for the yellow house’s lot when it came along almost two centuries later. The current owner of the old mansion and the land started selling off parcels, and new construction has arrived.

There are subdivision vibes creeping right up to the Niclas’s front door. He says they started building ten years ago, and they went fast. It’s Modest Mouse’s “Cowboy Dan” but make it Swedish.

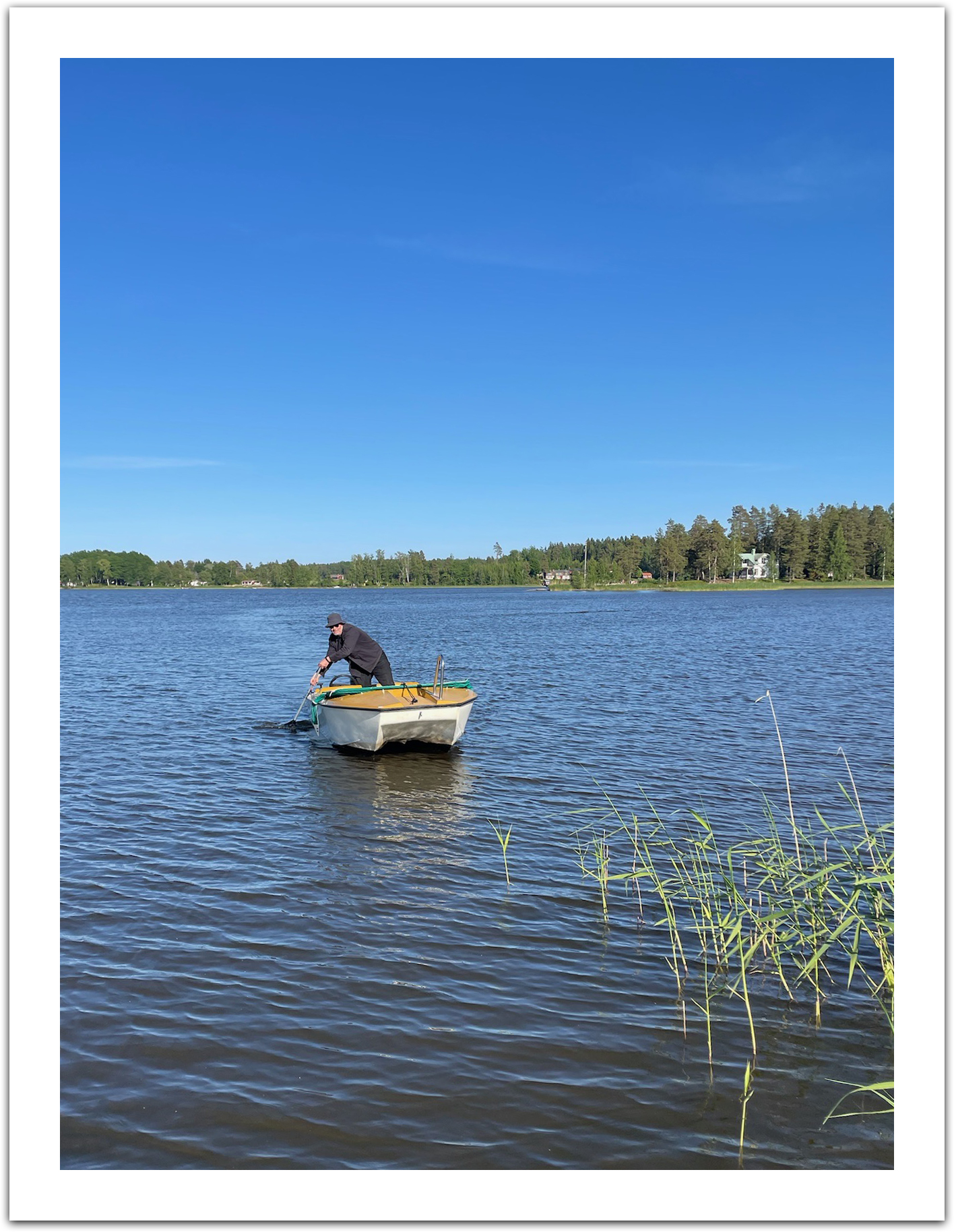

All that said, looking out the back of the yellow house, things are okay. The place sits on Lake Alstern, a small body playing second fiddle to Lake Vänern, Karlstad’s main attraction, the largest lake in Sweden.

He’s got half-done projects going in the back of the house, and a trampoline for the kids. Down the hill, there’s a two-lane road with a walking path. A row of modest homes sits along the lake. For now, in this direction, he’s protected from anything encroaching.

In the distance, on a small peninsula pushing into the lake, there’s a big house surrounded by trees and nothing. It’s gotta be one of the sickest pieces of property in Sweden. In the ‘40s, the doctor who owned the place gifted it to the local nurses for rest and retreat. Still today, they use it as they please.

Down on the lake there were no pontoon boats floating around blasting music. No dipshits tubing and partying. No noise.

“How come no one’s waterskiing?” I asked.

After a few seconds blinking, Niclas said, “Not allowed.”

Not allowed. As simple and clear as something could be, but casually blowing up my notion of civil society. Unsaid is the fact that people around here follow the goddamn rule.

Several days later, after returning home from the trip, I’d see a clip making its way around social media of a dipshit American politician sitting casually on the edge of his stupid desk speaking to the camera: “We’ve seen socialism. We know it’s bad.”

Niclas had three motor scooters; one Honda Silverwing, one a little wimpier than that, and a muscle-y one, almost a proper motorcycle, he’d bought used just before our trip.

We took a midnight ride through the edges of Karlstad, then the old historic bits, past the art museum where Niclas once had a show of his photos, past the house where his grandfather grew up, around the university where the buildings and the river reminded me of Iowa City.

Out near some fast food restaurants and a megastore, we hit a stretch of road Niclas called the drag strip, where we could get the bikes going as fast as they’d take us. We took turns up and back, zipping by with big smiles. Niclas and I laughed louder than the motors when we saw Brian speeding right up on the ass of a police car’s bumper. Swedish cop cars are so understated, he hadn’t recognized it as one.

The next morning, I took a walk on my own down the path from Niclas's house, and even with the encroaching mini-neighborhoods, you don’t need to go far before and you’re in fields of flowers and small houses.

I’d been hunting this particular piece of candy the whole trip. I now know them to be called Strawberry Dreams. My wife sometimes orders them from a shop in LA that focuses on Scandinavian sweets, and I wanted to try them from the source. I bought a scoop from the grocery in Rättvik, but they were terribly stale. When we got to Niclas’s place, he had the twins taste them. They agreed they weren’t right, and told us where to find good ones. When we took the scooters around on our second day, we hit the spot and I found perfectly fluffy Strawberry Dreams.

The first store I knew doing big scoops of candy priced by weight was Mr. Bulky’s at the Castleton Mall on the north side of Indianapolis in the ‘80s. It was a sugar delivery breakthrough, but the concept has gone downhill in American malls. This store in Karlstad has perfected that shit. They had it set up for an orderly line; scoops, bags, and buckets (!) at the front like silverware and trays, twist-ties and a place to recycle the scoops at the end before you hit the scales and register. Niclas said sometimes it’s a long snaking line.

I stocked up on the raspberry gumdrop called Gelehallon, too. Niclas told me they’re also called Little Titties. When we got back to the house, and I shared the fresh Strawberry Dreams with the twins, they pointed to the Gelehallons and said they’re very traditional.

“Hey let me ask you guys something. You ever heard ‘em called Little Titties?” They rolled their eyes, said no, acted embarrassed.

I thought I’d caught Niclas in a silly lie, the twins as my witnesses, but I heard him from the other room yelling, “No, not in English! You gotta translate it!” He brought me down to the office, dialed up a friend and made him confirm the nickname in Swedish.

Our last agenda item in Karlstad was a ride in Niclas’s new old boat. Like the supercharged scooter, he bought it used just before we arrived. This dude bought a scooter and a boat for our 24-hour visit to Karlstad, and thank god he did. We were taking the little craft on its maiden voyage under Captain Niclas’s command.

I have a core memory of the first time my dad took our family out on a boat he’d bought on a whim. We weren’t boat people, not even kinda, but we faked it for a few summers on the muddy-water reservoir in our neighborhood. It was a simple speedboat with comfy seats and a decent radio with a cassette deck, dark blue with sparkle specks in the paint.

On out first day on the lake, my dad found his way with the stick throttle, and was figuring out how to navigate the waves and wakes of other boats without jostling us all over the place. He got it up to full speed a few times, his wife and his kids in life-jackets riding up to their ears, hair whipping in the wind in front of nervous smiles. One of the American Dreams, at least where I grew up.

When it came time to return to dry land, dad asked me to sit up front and push off from the dock if he got too close. He came in fast, and I wasn’t strong enough to soften the blow. My little arms buckled, and the fiberglass nose of the boat cracked when we hit the the dock. This was the first time I felt sad for my father.

I thought about sharing this story with Niclas and Brian as we climbed into the boat, and as Niclas tried again and again to get the motor started. I kept it to myself. Eventually, it was running, and we were off.

We tooled around the perimeter of the lake a couple times, and then headed back. “Adam,” Niclas said, “make sure we don’t hit the dock.”

Things went into slow-motion. I had enough time to realize we were going too fast, had enough time to Niclas him we were coming in too hot, had time to wish I’d shared my dad’s blue boat crash story in advance, had time to say again that I thought we were gonna crash, and had time for Niclas to shrug and say, “It’s gonna be fine.”

I had an oar, not just my dumb arms, and I tried to break the boat’s trajectory by sticking it against the dock, but we came crashing in anyway, sideways. There was a thick rubber bumper attached to the wood. No damage. No cracks.

I know this will sound like something I’m adding for effect, but Niclas might have been more pleased had the boat gotten a ding or a crack, truly.

As we were packing up our shit to leave, I thought about the cities we’d seen, and wondered how much of a taste we really got for Sweden. I asked Niclas what it was like further north, and he told me at some point you go so far up there, the guys no longer say ‘yes’ to affirm. They just suck a little air into their lungs, a quick sip of oxygen soup.

Niclas, Beth, and the twins waved goodbye from the rooftop patio of the yellow house as we drove past on the road below, heading to Stockholm for our flight home.

A few days later, Niclas said the kids kept remarking to Beth how happy their dad looked with his friends at the house.