The opening chapter from my novel

"Okay look, I booked some Christian Rock shows, so I’m complicit in the least-cool American youth movement of all time."

I had this story in mind when I turned 30, but my attention shifted to booking bands full-time. My friend and music biz confidante Trey made me promise to write it eventually. “Don’t worry,” I said, “I’ll do it in my 60s.”

Early this morning, I turned 51, so I’m crushing my deadline.

RECOMMENDED IF YOU LIKE:

A NOVEL by Adam Voith

TAPE 1: February 1995

Okay look, I booked some Christian Rock shows, so I’m complicit in the least-cool American youth movement of all time. I wanted to show kids that select underground Christian bands could play toe-to-toe with normal, awesome, secular ones. It was my duty; my quiet evangelism.

This is The Christian Humper. I’m recording from the house where I live with my parents in Noblesville, Indiana, which is ever-expanding over cornfields on the north side of Indianapolis. If you’re listening, you’re part of a small crew. There won’t be many. If you dig it, please spread the good word. Make copies and pass them around. You have my blessing.

I’m making this tape primarily because my memory sucks dick. I tell these stories, hit blank spots, and start making stuff up—hiding holes and closing gaps. Eventually, I myself am unclear on what’s real. I booked my first shows five and six years ago, which means my recaps have lies, so I’m happy to capture them where they stand, get them on the record, freeze them in time to prevent further tampering.

The first show targeted my youth group with something other than Petra or Carmen or Newsboys or Michael W. Smith. An alternative to Bloodgood, Bride, and Sacred Warrior; all that weak Christian metal. The second show, more bravely, aimed for local punks and unsaved hardcore kids.

I blame most of this on Cole. I met him on a youth group outing to a rollercoaster park outside of Louisville. The trip was a recruiting tool, and our numbers were bloated, padded with kids from families who didn’t go to our church, or maybe didn’t go to church at all.

We loaded onto a chartered bus, and Cole walked past me down the aisle to the back row of seats. He had stringy hair, very long except on one side where he’d shaved it to the skin. He had on cut-off shorts, a Nuclear Assault t-shirt, and a hat that said SHIT HAPPENS in fat letters. A young believer among us had invited an obvious Satan worshipper along, and I can only imagine the huddled conversation our youth pastor and adult chaperones had outside the bus after Cole arrived.

Do we make him remove it?

Oh, I don’t think so. We don’t want to scare him off.

Pastor Peter, my daughter’s on that bus.

I didn’t talk to Cole that day, but that night on the drive home from Kentucky, and maybe it’s somehow because of the hat, I got handsy with Betsy Effinger—we called her Bets—under the permissively dim overhead lights in the bus.

A few weeks later, Cole turned up again at our church’s summer retreat. After the first night’s sermon, everyone splintered off in groups for games—basketball, euchre, flashlight tag—but Cole sat alone in the sea of empty folding chairs. He had a pencil which he stabbed over and over through the paper program from the service.

“You’re back,” I said.

I don’t think he recognized me, but he studied me, kept stabbing the paper, then sighed while he said, “I should be at Danzig and Soundgarden. They’re playing tonight, probably right now, at Bogarts in Cincinnati.”

It sounded like he was making up words. I was intrigued, but Cole was cagey, like he had secrets—like he was annoyed that I wanted his music secrets. With poking and prodding, he told me about more bands: Crimpshrine, The Mr. T Experience, Parasites, Libido Boyz. For the rest of the retreat, I half-focused on Jesus, and spent the rest of my energy pulling revelations from Cole. He’d packed tons of cassettes and CDs along with a boombox and headphones which I hogged during free time between meals, sermons, and small-group breakouts. He showed me a copy of MaximumRocknRoll with pages and pages of reviews, interviews, reports on local scenes, and advertisements for labels, bands, and other zines. Everything in there looked important. I asked Cole dumb questions—What’s a zine? What does 7” mean?—and he told me some of the answers.

Cole confessed that he was in a band called Decrepit. They’d broken up, but not before making a demo tape. He had one with him. I basically memorized the thing over the following twelve hours. The tape was called Infinite Falling, the cover a pen drawing of a storm cloud raining silhouettes of the three band members with DECREPIT in hand-drawn punky letters. The tracklist included songs like “Opulent,” “Racist Scum,” and “The Untruthful.” The lyrics were as basic as the titles, but I heard the melodies. The recording itself was garbage. I’d never heard music sound so shitty, and I loved it.

By the third day of the retreat, I was in the bathroom of the bunkhouse with a beard trimmer I borrowed from a chaperone giving myself a weird haircut. Cole was behind me over my shoulder in the mirror telling me it definitely did not look cool.

“Should I take more off this side? So it’s uneven?”

“Jesus Christ,” Cole said.

Who was in that mirror? This was only five years ago, but I couldn’t tell you anything I cared or thought about before that retreat. I’m sure I liked TV shows, had crushes on girls, had periods of devotion to certain candy bars, and looked after my grade point average, but gone by then were bike rides and frogs kept in cardboard boxes. Gone the thrill of birthdays. Gone were baseball cards, whoopee cushions, and chocolate milk. Gone childhood, but yet to be replaced with much.

Suddenly, Todd Hair was over my other shoulder in the mirror. Todd was the singer for our youth group band, Surrendered Heart. They were super into purple stuff. “Whoa, big change. Looks cool!” and immediately Cole aped him, making Todd sound like a toddler—wooks cooo-wool!—but by the time I was finished with the cut I was happy with the change, and even Cole shrugged and said it looked okay.

The final night of a retreat is a mystical motherfucker. After the adults and kids gathered one last time for the evening service, the youth group reconvened in a clearing in the woods behind the bunkhouse for a bonfire. We sang so many songs and we sang them so many times, repeating the choruses, new builds and harmonies arriving, rising, then receding. Between songs, we prayed. Kids re-dedicated their lives to Jesus. There were confessions of harmless things. People spoke shandalas and other gibberish.

I watched Cole out of the corner of my eye. He was a stone. Unlike the majority of us, he shed no tears—he didn’t even sing—but during a moment of reflection after a tireless cycle of “Our God Is an Awesome God,” Cole said the Sinner’s Prayer out loud.

Deeper in the night, Cole wandered off alone, up the path through the woods, back toward the dorm, and came back with his travel case of tapes and CDs. He torched the entire collection, tossed each album on the fire one-by-one as we belted out “Bring Forth the Royal Robe” in the round.

I wanted to reach into the fire and pull the records out, run back to the bunkhouse and hide them in my luggage. But I still wanted to save souls, put points on the board, so I let the music burn. Staring into the molten mess, face flickering with the flames, Todd Hair suggested each of us loan Cole some Christian CDs or make him a mixtape of our favorite Christian songs.

The next week, back home, my mom drove me to Romar, the Christian bookstore by the mall, and I spent forever going through the CD rack. I didn’t know what I was looking for, but knew DeGarmo & Key weren’t going to do it. Cole was not going to accept Whitecross. Was there a weird Christian band? Was there a cool one? The guy behind the counter was older, 100 years old to me. The pleats in his pants and the way he combed his hair gave me no hope for help.

I made my pick on shaky context clues. The band was called The Throes, a cool word I didn’t know, and the album title, All the Flowers Growing in Your Mother’s Eyes, sounded arty-farty. The cover had a close-up photo of a bouquet of daisies. It looked like a record by The Cure, but I didn’t know that at the time. I bought it for my new friend Cole, called him up, and asked if I could come over.

Cole’s bedroom was stark, and dark. His bed had a black comforter, black sheets, and black pillowcases, and there was nothing hanging on the walls. A dresser with deep, dark stain had a black stack of stereo components on top, and that was basically the only item in there. The room’s single window would’ve looked out onto the neighborhood, but Cole had super-glued the blackout shade to the frame so that he couldn’t see outside, ever. The flowers on the cover of the CD were the only color in the room when I brought it in, and for that reason, I second-guessed my choice when I handed it over.

Now I know the odds, the very bad odds, that a Christian Rock record is going to be good, so it was a lucky pick or a miracle. The easy comparison is R.E.M., but I didn’t know that at the time. Cole probably did, but we were both instant fans of The Throes. While we listened—over and over that first day—I fixated on the album insert which included lyrics, album credits, and three tiny headshots of the band members. Two guys, one labeled Singer, one labeled Drummer, and a girl. The pictures were in black and white, but you could tell she had bleached blonde hair and that her lipstick was either dark red or black. I asked Cole what a Basser was.

“She plays the bass guitar,” he said. “They’re trying to be funny.”

Our youth pastor was a young guy with a hot wife who still used her own last name. He was just out of college, not much older than we were, and deeply steeped in early-to-mid-career U2. He had us reading poetry and journaling and sometimes he talked about meditating. It’s unclear how he got hired and eventually, he was fired. The rumored last straw was his wife speaking to a prominent congregant couple’s daughter about her unplanned pregnancy and not immediately ratting the girl out. But before all that, before he was canned, I stood in his office explaining that he had to get this band, this Christian band called The Throes, to perform a concert at our church.

I don’t know how he secured the date, what he paid the band, how it was promoted, or who dealt with production. I can’t imagine what it took to convince the elders, but the band showed up as scheduled and played in our sanctuary, right there on the altar in front of the baptismal. Youth group kids stood up front and a clump of parents sat in the first few rows of pews.

The band sounded killer, better than the album, louder and more outsized, and although the bass player was wearing a paisley blouse and had pretty hair, it was a dude. A different Basser.

After they played, there was an awkward Q&A with the band. The questions, I’m sure, were the same ones they answered at whatever church they played the night before. They must have been so irritated. Their replies were acrobatic—the first band I saw walk atop the Christians in a Band, But Not a Christian Band balance beam. How exhausting.

Mandy Reed said, “What’s the spiritual message of your songs?”

Singer played it straight. “Well, the songwriting comes from our very normal lives. Most of our lives happen outside of the church, you know?” But no, no, most of us in attendance did not know. “We don’t have an agenda,” Singer said. “Anything and everything goes into the evolution of a song.”

“Excuse me,” Drummer said. “You do mean the creation of a song, right?” The band busted up at that, Singer slapping the table, new Basser stomping his feet.

When it was my turn at the microphone, I said, “I note that you’ve replaced a key member of the band?” New Basser said I wasn’t the first kid disappointed on the tour. “Well, thanks for coming, anyway,” I said. “I’m the guy who got the church to book you.”

“Oh man, thanks,” Singer said. “Next time you should book us at a club.”

One year later, with a different band, I tried to book a club. Still going to youth group on Wednesday nights, I pushed forward with my double life and on weekends I worshiped at the Knights of Columbus, the VFW hall, and the Broadripple Community Center, where local and touring bands played.

I met more music fans and bands, photographers, skaters, and zine makers. Hardcore kids with pants fifteen inches too big in the waist, goth rockers with their nightgowns over t-shirts, dipdog skinheads talking boots and laces, crust punks with the patches and a squat muscly dog, always a goddamn dog. There were kids running record labels and others screening t-shirts and 7” covers. On the edges where things overlap, I met pill poppers and acid droppers who went to raves instead of shows. There were free-spirit hippies smoking dope, and a pair of lesbians who loved me.

This was before the full-on explosion of alternative rock on radio and TV, like a year before the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” video, but weird was already making a push up from the underground, and I wasn’t alone in my drift from Christian Rock. At the start of the ‘90s, zealous A&R scouts at Christian record labels searched for born-again soundalikes of the bands leading young believers astray. A marketing genius came up with the tag Recommended If You Like for their facsimiles, and soon advertisements and reviews for Christian records all listed R.I.Y.L. comparisons.

You’re a fan of Depeche Mode? Check out Mad At The World. The Altar Boys will scratch that Replacements itch. Steve Taylor is your Talking Heads. The Choir will stand in for Echo & the Bunnymen. Parents won’t let you spin Slayer? Drive them crazy blasting Living Sacrifice.

Scaterd Few were an L.A. band—R.I.Y.L. pillars of indisputable cool like Bad Brains and Jane’s Addiction. Their debut album Sin Disease is my favorite Christian Rock record of all time, which is subjective, but without question it’s the most controversial Christian Rock record of all time. That’s a fact.

The record is a scorching mishmash of punk, funk, reggae, and jazz topped off with the enigmatic voice of a frontman who went by the stage name Rämald Domkus, a white guy with dreads who wore makeup to give the appearance of sickness or death. He was referencing Bauhaus, Bowie, and Lou Reed, of course, but I didn’t know that at the time.

Rämald’s range on Sin Disease goes from dungeon howls and growls to operatic caterwauls in the span of a couplet. His lyrics are verbose and confusing, mixing Old Testament tales, spooky references to ritualism, and stories of violence and addiction on the streets of Los Angeles. The album cover is a painting of Rämald looking like Jesus hosting 120 Minutes, his dreads in a pile on his head, a stand-in crown of thorns. The album title is scrawled across his chest. It’s hard to tell if he’s wearing a shirt—it could be printed on a shirt, but it might be carved into his bare chest. It’s ambiguous. The word was they played bars instead of churches around Southern California, and there were rumors that Scaterd Few smoked weed.

The record was released by a mildly-adventurous Christian label, but the chatter around the band’s lyrical content, questionable associations, and shady activities reached the top of the Christian music food chain, and the album was quickly banned by key distributors and yanked from the shelves of Christian bookstores. I got my copy before it was pulled.

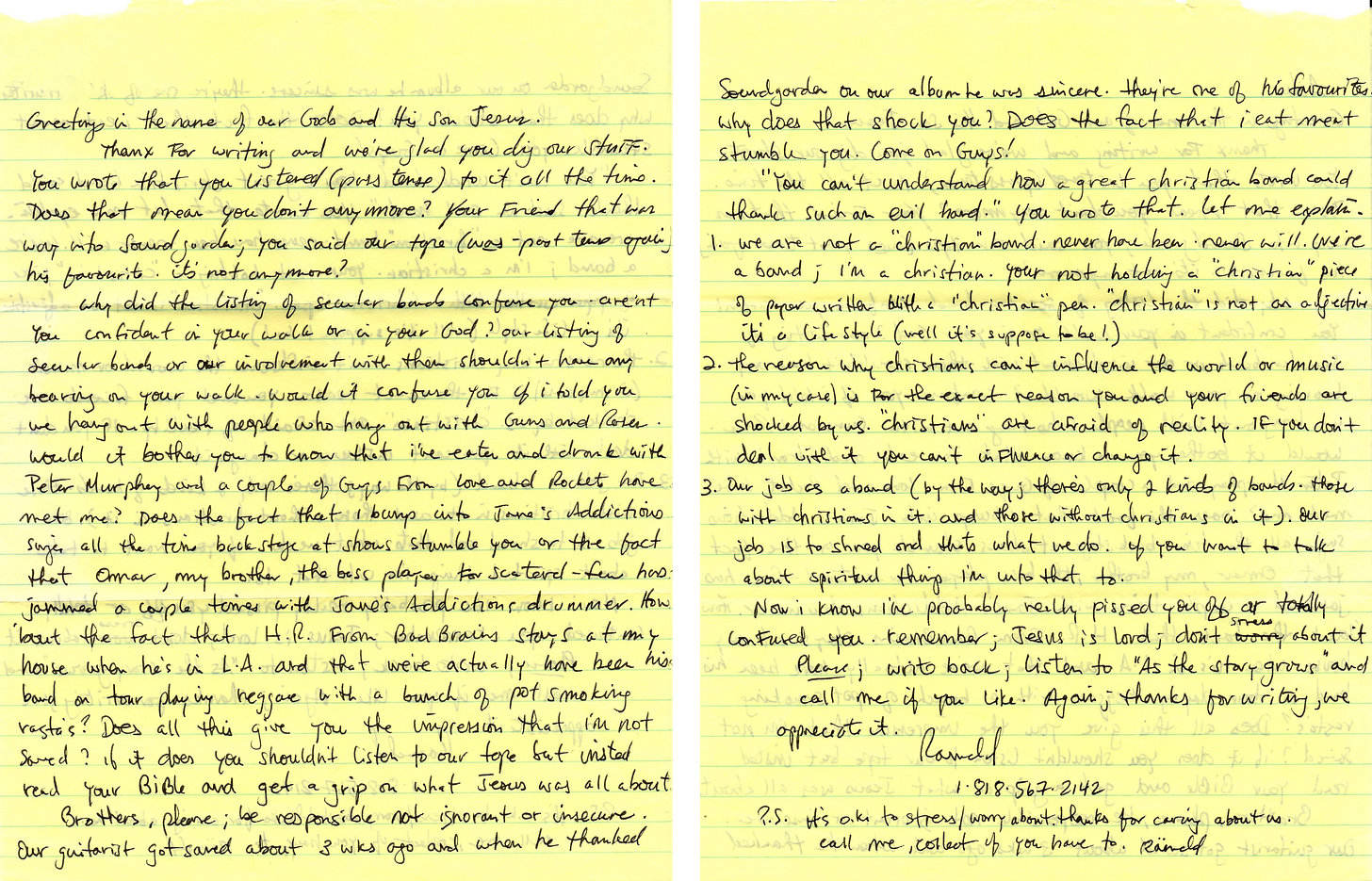

I listened to Sin Disease a bazillion million times, totally thrilled, totally hyped, but also bewildered. Yes I was playing the little seeker with secular music, but I was still keeping score. There were lines, when crossed, that still gave me pause. Scaterd Few worried me enough to send a letter to the fan club address in the liner notes, where they dared to thank non-Christian bands. I’m going to read you the letter Rämald sent back.

Brother,

Greetings in the name of our God and His Son Jesus. Thanx for writing and we’re glad you dig our stuff. You wrote that you listened (past tense) to it all the time. Does that mean you don’t anymore?

Aren’t you confident in your walk or in our God? Our listing of secular bands or our involvement with them shouldn’t have any bearing on your walk. Would it confuse you if I told you we hang out with people who hang out with Guns N’ Roses? Would it bother you to know that I’ve eaten and drank with Peter Murphy, and a couple of the guys from Love & Rockets have met me? Does the fact that I bump into Jane’s Addiction’s singer all the time backstage at shows stumble you or the fact that Omar, my brother, the bass player in Scaterd Few, has jammed a couple times with Jane’s Addiction’s drummer? How about the fact that H.R. from Bad Brains stays at my house when he’s in L.A. and that we’ve actually been his backing band on a tour playing reggae with a bunch of pot smoking Rastas? Does all this give you the impression that I’m not saved? If it does, you shouldn’t listen to our band but instead read your Bible and get a grip on what Jesus was all about.

Brother, please; be responsible, not ignorant or insecure. Our guitarist got saved about 3 weeks ago and when he thanked Soundgarden on our album he was sincere. They’re one of his favorites. Why does that shock you? Come on guys!

“You can’t understand how a great Christian band could thank such an evil band.” You wrote that. Let me explain:

We are not a “Christian” band. Never have been, never will. We’re a band; I’m a Christian. You’re not holding a Christian piece of paper written with a “Christian” pen. “Christian” is not an adjective.

The reason why Christians can’t influence the world or music (in my case) is for the exact reason you and your friends are shocked by us. “Christians” are afraid of reality. If you don’t deal with it, you can’t influence it or change it.

Our job as a band is to shred and that’s what we do.

Now I know I’ve probably really pissed you off or totally confused you. Remember, Jesus is Lord. Don’t stress about it. Please write back, and call me if you like, collect if you have to. Thanks for caring about us, we appreciate it.

Rämald

(818) 567-2142

There it was again. Did you see it? He was more angry than The Throes, and Rämald got self-righteous and name-dropped, but essentially the same response. Time and shame passed by, and eventually I called the number at the bottom of the letter. On the phone, Rämald was patient and sweet, and he let me stumble through an apology. He boasted more about who he knew, the bands he saw play out in L.A., but he asked me about my life, too. I exaggerated my local standing and claimed I brought cool bands to town for shows regularly.

“You got a good scene there?” Rämald asked.

“Oh yeah,” I said. “Big scene.”

“You think Scaterd Few could come play?”

“You should absolutely come play,” I said. “We could do it at a club.”

“You got rock clubs?”

“Totally.”

“Real ones?”

“Totally real ones. We’ve got tons of rock clubs,” I said, though I couldn’t name one. All the shows I’d seen outside of churches and Christian coffeehouses were at all-ages spots or in someone’s basement. I assumed those would not do for a band who hung out with a guy who once walked past the third singer of Black Flag in Hollywood.

“We’re playing Cornerstone Festival this summer,” Rämald said. “Is Indiana close to Illinois?”

“Super close,” I said. “We’re actually the state right next door.”

He asked whether I paid a guarantee, and I answered yes too quickly. With zero knowledge of the costs to produce a proper concert, I threw out a number I thought would be enticing. Rämald answered quickly, too. “Brother, if you’ve got $500, we’ll see you in Indianapolis.”

I made two columns on a piece of paper—WILL COME / MIGHT COME—and squeezed my brain for a hundred names to fill the first one. My math was missing many numbers like venue staff and advertising, so I just went like this: 100 WILL COMEs x $5.00 tickets = $500 for Scaterd Few, all good.

But I was struggling for even 50 WILL COMEs, which included many kids from my youth group, never mind that most of them would hate this music and a bunch of their parents wouldn’t let them go to a show outside the church. Most of the non-Christian punks started in the MIGHT column, but I bumped them, hopefully, to WILL along with friends of friends and, eventually, kids I hardly knew. Even then I didn’t hit the target, so I put my faith in Scaterd Few’s draw outside my circle. Surely there were Christian Rockers on the other side of town I’d never met. Obviously Christian Rockers would road-trip in from Valparaiso, Ft. Wayne, and Evansville.

Booking The Throes was easy. The sanctuary and staff were free, and the artist fee was a dip in the church coffers. I saw money pile up in the golden plates they passed around each Sunday. The Throes were petty cash.

To find a proper club for Scaterd Few, I asked Decker Carr to help. Decker was a Weeble-Wobble-shaped dude who managed a local Christian punk band called Three Nails. He wore a long earring with a dangling cross that was always tangled into his ratty, collapsing blue mohawk. He was missing a key tooth, but the effect was soft, not scary.

Decker was a big fan of Scaterd Few. He was thrilled to hear about the letters and phone call with Rämald, and said knew a dude at The Ritz Music Hall, a venue rich in history with touring punk and metal bands, including a legendary gig with DRI in 1987 that ended in a miniature riot. Decker secured a date, said he’d deal with the club and lend a hand with promotion. He knew about the $500 commitment I’d made, and if he was worried about covering the dough, he didn’t let on. Christian Rock is necessarily optimistic.

For credibility and to attract non-Christian kids to the show, I asked a cool local band to open. I did not tell them much about Scaterd Few, only that their singer was known to frequent a diner on Sunset Boulevard where a waitress worked who once fucked around with Mike Ness from Social Distortion.

When Decker said he’d help promote, he meant he’d hand me a single copy of a hand-drawn flyer he made with a Sharpie. My dad took me to his office after hours and we burned off hundreds of copies on the company Xerox machine. It was a nice moment between us. Dad was stoked to be involved and acted like we were on a clandestine mission.

I passed out flyers at youth group and school, stapled them to telephone poles and community bulletin boards, and hung them in the window at record stores and pizza shops. They’d last a while before getting torn down, blown away, or covered by a flyer for another show, but I carpet bombed the city several times. I was proud of my first promotional blitz, sure it was filling the WILL COME column with more names.

The capacity of The Ritz Music Hall is 400 people. We sold 14 tickets. If you count those people in the opening band (5), the skeletal venue staff (4), the guest list, which included only the members of Three Nails (4), Cole (1), Decker and me (2), and there might have been 30 people through the room that night, but never all at the same time. A lot of people left early.

My memories from the show are decidedly not of the band shredding, the one job Rämald claimed they had. The performance was uninspired, though I can hardly blame them. Between songs, Rämald looked out to the pitiful audience and I was able to imagine the room from his perspective, the vastness of an empty concrete floor. “So Indiana,” he said. “The heartland. You guys into Christian Cow Tipping?”

I tried to start a circle pit. I was joined by three youth group kids, unselfconscious as they come. No cool kid would have joined, but that didn’t stop me from reaching out and pulling the guitar player from the opening band in with us. I felt his lack of commitment, his noodle arm, immediately. He skipped around once, half-assed, before dropping out and heading for the door.

Leading up to the gig, I allowed myself to fantasize a celebratory hang with the band. Sweaty and satisfied after a packed-out show, I’d talk more with Rämald, pick up where we left off. I’d thank him for coming to town, and he’d thank me in return for booking the best goddamn show of the tour.

I met Rämald briefly before soundcheck. I told him I was the letter writer, the phone-call guy. He clicked a smile with half his mouth, a poppy seed stuck in his teeth, then came in for a hug and said we should talk more after the show. At that point, together we believed a good night might arrive.

Instead, after the band played I hung back, crushed by the weakness of the whole scene. Decker told me early in the night we weren’t going to have the money to cover the guarantee. The ticket sales didn’t cover basic club costs, which meant nothing was going to the band. I lurked behind Decker as he told Rämald we were short.

“How short?” Rämald said, looking over Decker’s shoulder at me.

“At the moment,” Decker said, “I’m afraid we don’t have any money for the band, and we owe the club some money.”

“That was a guarantee you offered?” Rämald said, eyes still on me.

“It was,” I said, “and I’m sorry.”

“For what?” he said. “A guarantee’s a guarantee, brother. A word is a word, so you’ll find a way.” Then he winked and walked backstage.

The Throes knew what they were getting into; they knew what playing a church meant. They were paid by check before the show and enough people came for it to feel half-real. My failure with The Throes was a private one. Nobody knew I booked it to meet a girl who wasn’t in the band anymore, but this time, I was on display. I’d talked a big game to Rämald about Indiana, pitched the local band on the opportunity to find new fans, and was on a limb with my friends after hyping up how sick the show would be.

Decker and I, along with a few sympathetic others who remained, emptied our wallets for whatever we had, inching close to $80. There was a random older dude in a business suit milling around who claimed he’d never heard of either band, loved music but hadn’t gone to a concert in ages, so came on a whim. He hit the ATM and came back with a hundred bucks like a saint. There was a nearby head shop that bought and sold used music and stayed open late. I took tapes and CDs from my car and sold them, bringing in another $60. Someone suggested a prayer circle. Perhaps the Big Guy would turn photocopied flyers into twenty-dollar bills. We offered up words to the sky, but no miracles arrived.

Meanwhile, Scaterd Few lumbered around their van drinking canned beer and chain-smoking cigarettes. The drummer, who had not said a word to anyone since the moment they’d arrived, was now muttering for all to hear. “Very cool. Very Christian. What would Jesus do? Oh yeah, he’d rip off the touring band for sure.”

Obviously it was on me, so I called home, woke my dad up and asked if we had cash at the house and said I’d pay it back over time. I drove home, drove back, and gave the money to Decker. I couldn’t bear to take it to Rämald myself.

Once they were paid, the mood changed, and Scaterd Few ended up crashing at Decker’s house that night. I didn’t go—too mortified to hang—but heard the drinking and smoking went deep into the night.

I should note that after a four-year wait, Scaterd Few released their second full-length last year. Recommended If You Like: wildly disappointing follow-ups to perfect records. I listened again before making this tape to be sure, and indeed the album blows. Avoid it completely. Pretend they made one album and quit.

Hi, Adam: this hit so many personal marks (Sarx?) for me. The producer of Rock That Doesn’t Roll (college friend plus I did the score) recommended you to me, particularly your section on Alan Aguirre and SF.

Also - I grew up in the DC area (of the Body) so saw The Throes many times. Really sweet people and - for someone like your pal, Cole, who had just burned all his albums - a godsend for a kid who had just thrown out all of his Dischord records (still pains me - I winced reading that part).

1000% agree that Sin Disease is the best Xtian album ever made. No contest. (Well, maybe “Michael W Smith 2”… I kid.)

Years later, my touring band (also a band of Christians playing in a “secular” band) got the chance to open for Aguirre’s new band, Spyglass Blue. I hated the band - they were even worse live - but I was excited to get a chance to pick Allan’s brain and compare notes. He was so bitter, vindictive and rude, it almost took my breath away. Like, whoa… okay, guy. Yeah, your brother once jammed with Perry Farrel’s orthodontist or whatever. (The name-dropping references really made me laugh.)

So… you were HR’s backing band and you’re gonna shake down a teenage church kid for 500 bucks?

Kind of says it all right there.

Anyway, this was a fun (and cringey) read - so many shared evangelical rites of passage - but I look forward to tuning in.

Very happy to see this out in the world. Cannot wait to read more....